Differential Privacy in Today's AI: What's so hard?

Posted on Di 06 Januar 2026 in ml-memorization

In the last article in the series on addressing the problems of memorization in deep learning and AI, you learned about differential privacy and how to apply it to deep learning/AI systems. In this article, you'll explore what can go wrong when using differential privacy training in deep learning and open questions around using differential privacy to address memorization in machine learning.

In this article, you'll confront some larger issues in applying differential privacy in deep learning systems. These issues span beyond tuning parameters and applying technical thinking into how organizations function and what privacy means to us as individuals and society.

You'll address the following questions:

- What data needs to be protected in the ML lifecycle?

- Is your data representative enough to learn while using DP?

- Can some tasks ever be private?

- How can you work interdisciplinary to develop real use cases?

Defining sensitive data and governing its processing

You might recall from the last article that a group of Google researchers pretrained a BERT model (LLM) using differential privacy. This isn't as common as you think, actually in many instances of using differential privacy at scale, practitioners first pretrain or train a base model on "public" data and then later fine-tune the model using differential privacy.

There are certainly accuracy benefits when doing a part of the training without differential privacy. Many companies claim scraped data is public anyways, so there's no problem training on it. But, is all scraped data from the web really "public"? Are there any privacy problems with pretraining on internet-scale data scraped from the web?

Tramèr et al. (2024) released a position paper calling for a more nuanced approach to what data is considered public. The authors cite a real example where someone's phone number was memorized in a LLM. When the person asked for their data to be deleted, the company responded that memorization wasn't possible because they fine-tuned with differential privacy.1

What actually happened was that person's number was exposed during pretraining on "public" data due to a file being on the public internet with the person's information. The model memorized it from the "public" pretraining and no amount of differential privacy fine-tuning mattered (in this instance).

The paper also highlights a GitHub user who accidentally published their cryptocurrency wallet information. When they realized this, they deleted it; however, Copilot already memorized the string and someone extracted that information and emptied the wallet.

So is web scraped data really "public"?

The authors:

Someone may post their contact information along with a research publication with the intent that it is used to contact that person about details of the publication. Sensitive data about individuals could also be uploaded to the Internet unintentionally (or by third parties privy to this information). As a result, people often underestimate how much information about them is accessible on the Web, and might not consent to their “publicly accessible” personal data being used for training machine learning models.

In both of these cases privacy wasn't considered as part of the entire machine learning life cycle. To properly address privacy, you'd need to look at the entire system: from dataset collection, preprocessing, embedding models and the actual AI/deep learning system.

Beyond deciding which data should be used with or without differential privacy, there are open questions around how to best apply differential privacy in machine learning setups. One of which is the ability to reason about the impact of differential privacy on groups in the dataset.

Is the data representative enough for error?

For training deep learning, you need to evaluate the training pipeline in its completion alongside deciding what data you have for the task. But before you know whether your training will even work, how can you decide if you have the right data to learn? And what do you already know about what you need to learn?

Tramèr and Boneh (2021) found that to reach the same learning accuracy a differentially private deep learning model might need an "order of magnitude" more data.

How come? Well, if the model cannot memorize or learn from just one example, it must process many examples of that concept to learn it privately.

If you studied machine learning or have worked in the field for some time, you might have come across PAC learning theory or universal learning theory. These theories help the field discover more about how machine learning works, how to make it more efficient, how to evaluate learning bounds and determine what data is required to appropriately learn. Too often, learnings from this field are not integrated into how today's AI/ML systems are built. This means you are often doing things more inefficiently than necessary.

There's been significant evolution of the overlap between learning theory and differential privacy. For example, there are bounds as to what can be learned (PAC theory) when it comes to using differential privacy on certain complex distributions. There's also mathematical proof that all distributions are differentially privately learnable although they might not be efficient.2

One thing worth considering when choosing datasets and collecting other people's data for deep learning is that the underlying distribution and sample complexity impact whether you can learn privately. You already learned this by understanding that complex classes or examples are prone to memorization and hard to unlearn, but I want you to consider the problem from a different perspective.

In an applied setting: If you don't have enough different and diverse data, or if you don't have a well-defined problem space and can't find data that adequately represents that problem, you probably won't be able to learn privately. And to be honest, you might not be able to learn even well without differential privacy!

This means spending time to understand your training data and how it represents the task you are trying to learn. This means looking critically at benchmarks and deciding if the data really represents the task.

My advice: think through your problem and task deeply. Figure out what you actually really need to learn and what is superfluous. Then determine if you can actually simulate, collect or produce data that matches that requirement. This will help you not only learn privately, but also more efficiently.

Evaluating this as a team can spark useful conversations about what is worth learning and at what cost.

Is it possible to train this model privately?

It can be difficult to determine if a deep learning/AI model can be private given the particular use case and dataset. Is it private if the model memorizes sensitive data even with differential privacy due to repeated exposure? This can happen even with differential privacy if the data has multiple sources with the sensitive information.

Brown et al (2022) asked this same question specifically for language models. The authors argue that Nissenbaum's contextual integrity should apply to language models. Nissembaum's theory says each user should have autonomy about how, where and in what context their data appears. The authors argue the only data that matches how LLMs are used today is data intended to be freely available for the general public.

Text origin and ownership is often difficult to define, which is a key decision to appropriately apply differential privacy. For example, as you learned in the last article, to do appropriate privacy accounting, you define how much one person can contribute to the training. This is surprisingly difficult for text data because sometimes someone is quoting another person, or paraphrasing or referencing. Or someone may use different accounts or handles but be the same person. How can you define authorship well enough to apply differential privacy?3

The authors also ask: in what context did I write this and to whom? Text is easy to forward, duplicate and share in new ways. Someone can forward my email, quote me or also paraphrase something without attribution. This means that the original author and intent is easily lost, and person-level attribution and accounting ends up being quite difficult.

The memorization that can happen, even with state-of-the-art differentially private language models, affects real lives. In 2021, researchers found that people's names appeared alongside medical conditions that were extractable from clinical notes that were leaked online and appeared in the training data.

The authors' thesis can be applied beyond language since digitized data easily loses its sources and context. Nissenbaum's theory states that the digital world doesn't translate well our human understanding of privacy. It's easy to accidentally overshare, to post something that goes beyond its original context or to also take someone else's data and share it in a way they never intended.

For those of us working on this problem: what large language models can truly be "privacy preserving"? When can you ensure the guarantees match the real-world concerns and context? Is example-level good enough for the problem at hand? Do we need to think through attribution at a higher level?

In my opinion, the field would benefit from more multidisciplinary teams having these discussions. This would help:

- ensure researchers are working on real-world problems

- align legal understandings with technical ones

- spark social conversations around what data goes into AI and what protections are expected

- develop new model types: ones that can attribute sources for example

- create new business models: ones where people opt into having their data used either for compensation or for co-use

Privacy is by-default a human understanding, and the best bet on achieving real privacy in ML/AI involves putting humans at the center of the conversation.

Developing multidisciplinary thinking

Defining the use cases, tasks and training data is rarely multidisciplinary. In many organizations, product defines the use cases and sends them over to the data or machine learning team, or even hires a third party provider to do so.

This game of telephone means that sometimes the use case and task are not even well aligned or defined with the data and tools available. When this happens it often also means that the privacy and security requirements end up being misunderstood or not well translated.

Even when working with third parties, it could add to the product performance and the privacy and security requirements by having healthy conversations and co-designing in multidisciplinary teams.

Ideally the product lifecycle includes privacy, security, machine learning and risk stakeholders from the beginning. It could look something like this:

- Start product ideation as a multidisciplinary team

- Threat model and provide privacy engineering input based on early architecture, data and design choices (nothing built yet)

- Begin model, data and software development using identified privacy technologies and best practices

- Evaluate models based on specs from product, privacy and security

- Finalize model candidates and integrate them into stack

- Purple team models and perform privacy testing

- Tweak guardrails, controls and model choice based on attack and evaluation success

- Launch after sign-off from the multidisciplinary team

- Check-in and re-evaluate based on changing risk and model landscape and learnings from other products

By testing privacy technologies like differential privacy as you go, the organization and involved teams gain knowledge, understanding and experience on how to use them effectively. Eventually there will be enough experience to expedite decision making on design patterns and to effectively integrate privacy and security technologies into common stack choices and platform design.

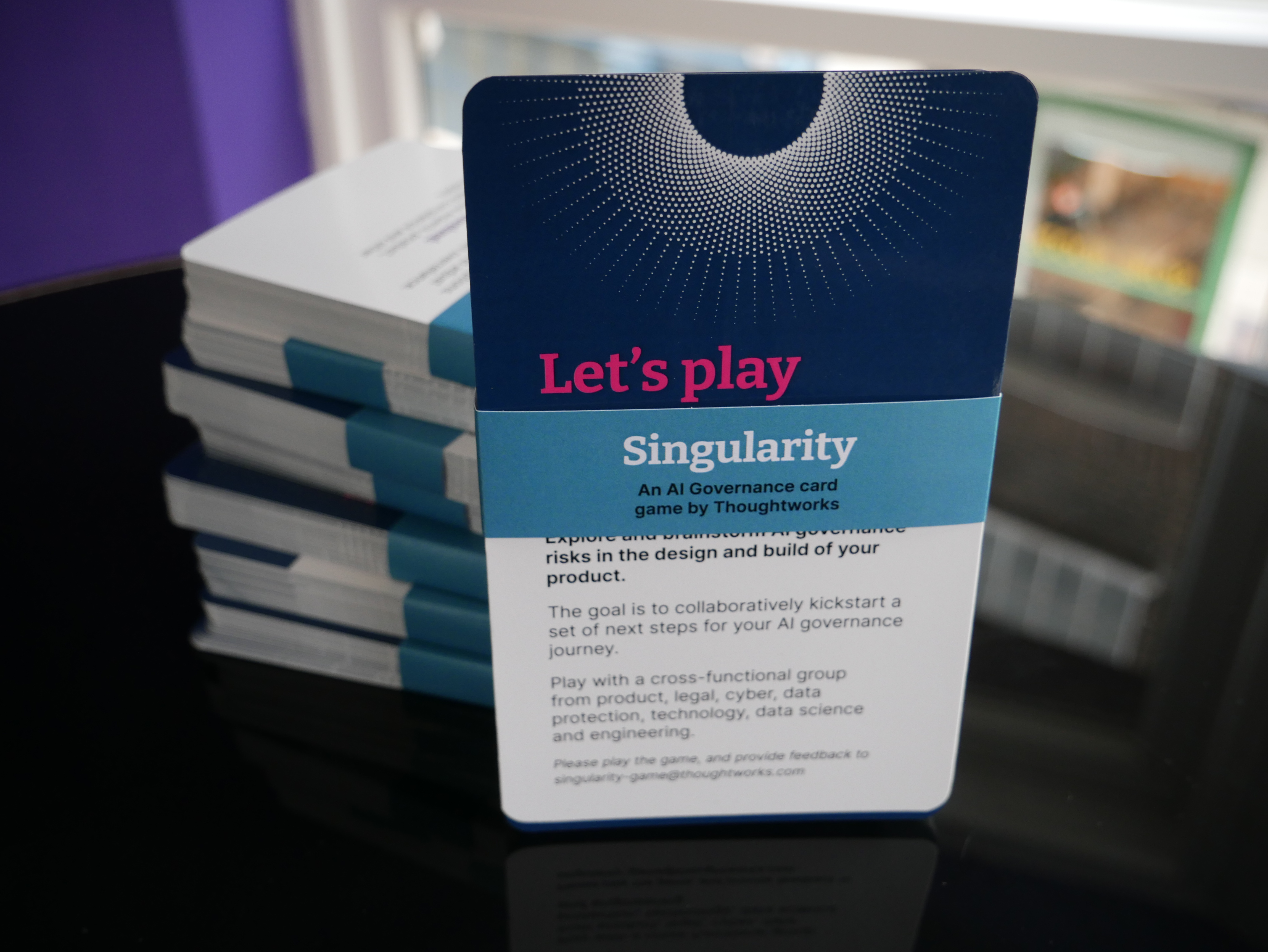

I helped co-develop the Thoughtworks Singularity card game as a fun way to practice multidisciplinary threat modeling and risk assessment alongside my colleagues Jim Gumbley and Erin Nicholson.

I helped co-develop the Thoughtworks Singularity card game as a fun way to practice multidisciplinary threat modeling and risk assessment alongside my colleagues Jim Gumbley and Erin Nicholson.

By involving many stakeholders in risk evaluation and mitigations, you'll also develop a more mature approach to data and AI. There's something special about evaluating risk as a team because understanding risk also means actually building a deeper understanding of the system and its parts. As a team you'll learn more about how models work, when they fail and what you should do about it.

In the next article, you'll investigate what is already known about auditing privacy and differential privacy choices in deep learning systems, and explore what isn't yet known or regular practice.

-

This is fairly common practice and a good idea if you are fine tuning and not actually pretraining your own models. You can follow the same advice from the last article or in my book on the topic. ↩

-

If you have an hour to spare, I highly recommend this lecture on the topic from Shay Moran, an expert in studying learning theory and differential privacy. ↩

-

This is why many deep learning models try to protect using per example privacy, but it's a very good point that this will certainly leave prolific creators, writers, journalists and famous citations overexposed by design. ↩

-

If you need an example of how to get started, check out my Probably Private YouTube series on Purple Teaming AI Models. ↩