Differential Privacy Parameters, Accounting and Auditing in Deep Learning and AI

Posted on Fr 06 Februar 2026 in ml-memorization

You've learned in the last few articles about how differential privacy works and some of the common pitfalls of actually using it in deep learning scenarios.

In this article, you'll learn about tracking differential privacy: through parameter choice, accounting and auditing. If done well, these choices and methods reduce memorization in deep learning systems.

How do the privacy parameters in differential privacy work?

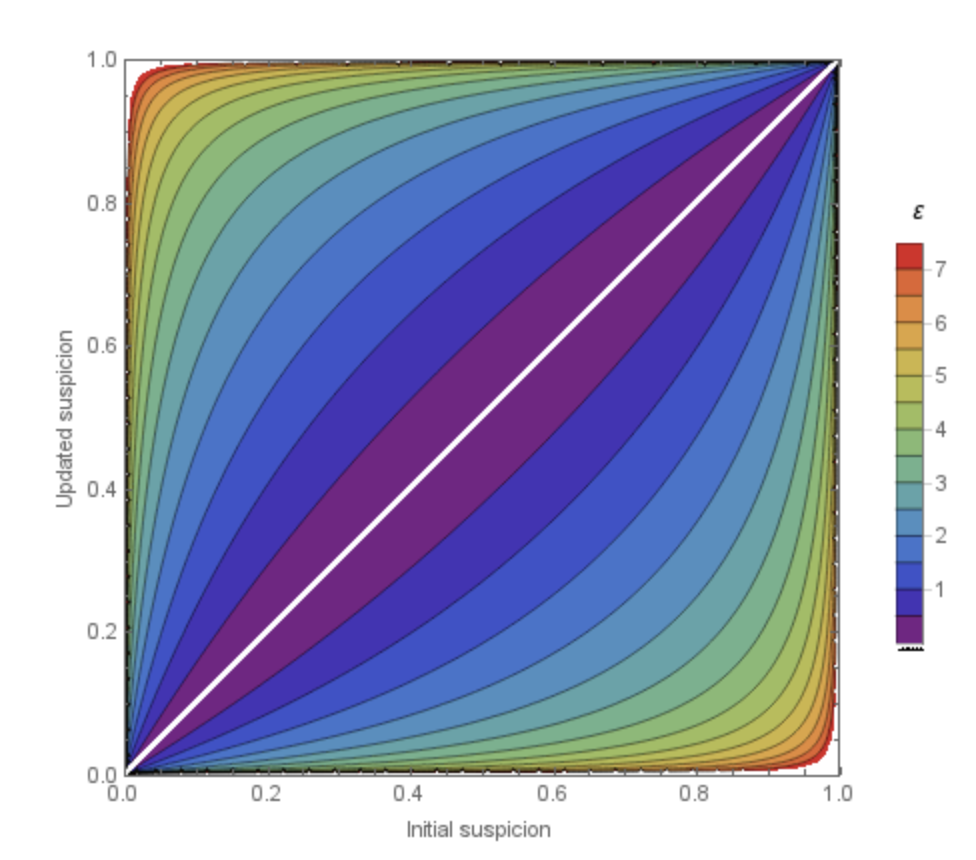

As you likely recall from the previous article, differential privacy has privacy parameters in the definition. Reasoning about these parameters is something a team really has to do in practice to develop an understanding of their meaning and what they measure. As a starting point, however, I recommend this useful chart generated by Damien Desfontaines.

Updated suspicion based on epsilon choices

Updated suspicion based on epsilon choices

This chart assumes a sophisticated attacker who attempts to determine which database they are interacting with and update their knowledge based on the response.

The chart shows the initial suspicion across the x axis. This can represent what the attacker either has already learned about whether the person is in the dataset or not, or what they learned based on a previous query.

Then, after they query a differentially private database, they can update their suspicion. The y-axis shows the bounds of the information they get in return which depends on the epsilon choice. It is never guaranteed that they learn the "maximum" of the bounds, but instead guaranteed that they learn within the bounds -- it could be that with one response they learn nothing.

The different colors in the chart represent different choices of epsilon. The bounds can be quite small with a small epsilon and much larger with a large epsilon. Choosing an epsilon of 5 is much different than an epsilon of 1. These bounds are the guarantees that differential privacy uses to protect individual information. You will also use these bounds to determine what is the balance between the information you are trying to learn and the information you are trying to protect.

If you are doing something like preprocessing or data exploration, you usually choose an epsilon upfront and split it unevenly across your queries, so you can get a bit more information from some queries rather than others. Spending more of your epsilon on a query results in a more accurate, informative and therefore less private response.

Any time you repetitively query or process data in your analysis, you track this epsilon (or other parameters depending on your definition) so you know the entire epsilon spent.

In today's differentially private deep learning libraries, there are two approaches to epsilon choice. One is to choose an maximum epsilon, which will lead to early stopping. The other is to track the epsilon and to keep training until a certain accuracy is reached. The second choice means that you could end up with a higher epsilon than you originally thought, but you can also decide to throw away the model and retrain (which means you wasted time and compute, but you hopefully learned something about your data).

So how does the second process work in deep learning? How can you track the epsilon if you're not setting it in advance?

An Introduction to Accounting

If we don't know exactly how much epsilon we have to spend, we need to measure how much we did spend! In the case of deep learning, this is actually often how we track the privacy parameters. In each batch during the DP-SGD training the process calculates and calibrates the noise based on characteristics of the batch. This calculation also estimates the epsilon, and that is tracked by an accountant.

Already in the original definition of DP-SGD Abadi et al. there was an accountant to track epsilon spent. This accountant is called a moments accountant. This approach is still used in both JAX Privacy and PyTorch's Opacus for differentially private learning.

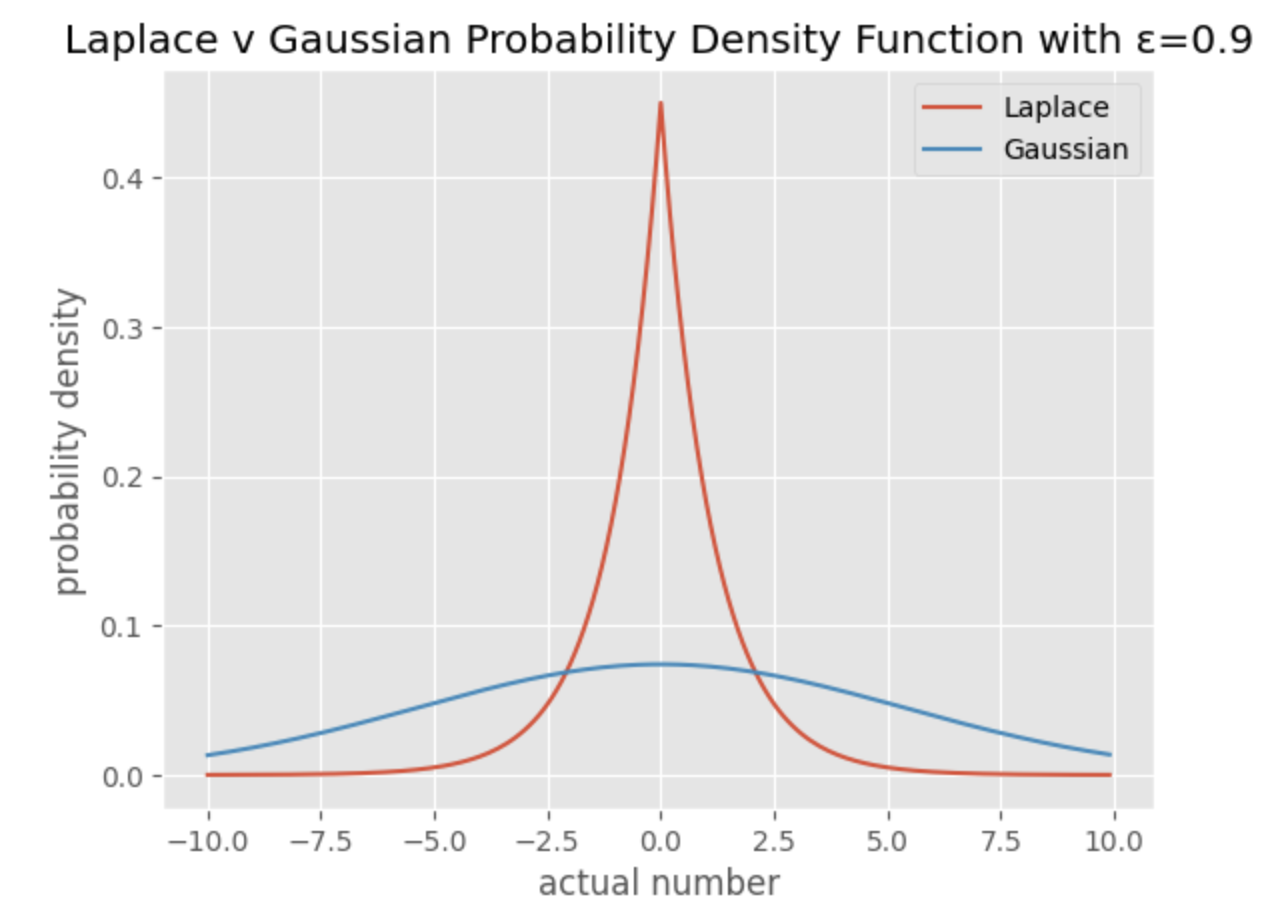

To appropriately calculate the bounds and approximate the epsilon the authors needed to understand the behavior of the noise they were using. The authors were interested in Gaussian noise as it has some nice properties when compared with other distributions and some benefits when looking at how deep learning systems work (i.e. when working with regularization, recognizing patterns and managing embedded spaces).

I highly encourage you to play with Liudas Panavas' interactive chart to explore more values of epsilon.

The problem with Gaussian noise compared to, say, a Laplace distribution is that it has a higher chance of ending up with less noise because of the gradual tails. If you end up too far in a tail, you could essentially add 0 noise, nullifying the privacy guarantee. If you want those tight bounds/guarantees like in Desfontaines's chart, how do you appropriately calculate the chances you end up adding noise from the middle, the 10th percentile, the .05th percentile?

Abadi and coauthors were developing some interesting work on learning theory around differential privacy and they had the idea to use higher order moments (like 3 for skewness and 4 for kurtosis) to better understand and therefore bound the probability of catastrophic failure (i.e. almost 0 noise). By studying this both via working through the math and theory but additionally testing their implementation, they were able to develop better bounds for Gaussian noise in deep learning.

Let's walk through how the moments accountant works:

-

Based on ideal spend for the two parameters (epsilon and delta) and the clipping value (which is the gradient norm of the mini-batch), a Gaussian distribution is formed to add noise to the clipped gradient. These parameters inform the standard deviation of the Gaussian noise distribution.

-

Several moments (i.e. 3 and 4, for example, but you can go up to a very high number of moments) are recorded for that noise distribution and stored by the accountant.

-

Training continues, performing steps 1 and 2 for each minibatch.

-

At the end of an epoch, sum the moments accumulated and calculate the upper bounds of those training rounds based on those values. This can be done to reverse the amount of epsilon and delta spent in that epoch.1

-

If the target epsilon or delta is reached, you can stop training. If target epsilon or delta are not reached, training epochs can continue. Usually the accountant will also display the information via a log message per epoch.

This moments accountant and the Gaussian bounds calculation eventually led to more advanced definitions, such as Renyi differential privacy, which is now the standard for today's deep learning implementations.2

Okay, so how do you make sure that the moments accountant is doing things appropriately? Similar to difficult problems like cryptography, you never want to write your own unless you are working with actual experts. Even (or especially because) the experts know, you gotta audit!

Auditing v. accounting

Let's disentangle two separate concepts: auditing and accounting. Accounting is keeping track of the privacy parameters for a given experiment, process or query. In your case, this is likely your training or fine tuning. Usually this means you:

- set an ideal budget

- track it via some accountant (like the moments accountant)

- ideally stop processing when the budget is reached

As you already learned, sometimes you might actually stop at a given model performance (i.e. error, TPR or FPR or some other metric). At that point you can also use the accountant to decide, is this privacy "enough" to use the model?

Auditing, however, is actually making sure that your differential privacy mechanism is working properly and also that your accountant works properly. This is testing that the libraries and tools you are using are working properly, but can also cover if you are using them properly (i.e. looking at the entire setup and ensuring the parameters, processing and tools meet the requirements set).

Let's dive deeper into auditing so you can know how to choose tools that are safe, have been tested and that also fit your needs.

Third-party auditing of tools is necessary

Auditing your tools and accounting makes sense. The entire privacy guarantee is based on whether the differential privacy libraries:

- theoretically prove what they're doing is sound

- implement that theory into software properly

- didn't accidentally introduce a new vulnerability

Similar to other difficult problems like cryptography, developers need to make sure their implementation is tested by other experts and regularly updated with new insights, theory and attacks.

I also recommend reading Damien Desfontaines' article on 3 types of privacy auditing. I'm talking about definition #3 here.

In Debugging Differential Privacy: A Case Study for Privacy Auditing, the authors showed how easy it is even for domain experts to miss important nuances in differential privacy in deep learning. By auditing a new approach, they uncovered a bug in the implementation which severely underestimated the epsilon and resulting privacy leakage.

Does this make the original authors "bad" or any less experts than they were? No. It proves without robust auditing from external parties it's difficult to ensure you have "seen" everything. This is why the field of cryptography has embraced open-source, open auditing and even incentivized auditing as an industry--to attempt to catch these mistakes and ensure the security guarantees are real. Even then, it's possible to get this wrong, such as what happened with the OpenSSL Heartbleed Vulnerability.

To audit the incorrect differential privacy implementation, the authors ran a sophisticated membership inference attack where they inserted specifically poisoned examples which acted as canaries. Then they attempted to find these canaries with sophisticated membership inference attacks.

To build successful canaries, they identified useful starting examples by testing canary creation with a subsample of the training data.3 Then they trained 10K models on different subsets of the poisoned vs non-poisoned examples--all supposedly with appropriate differential privacy granted via the new implementation.

They admit that training 10K models was overkill and they could have probably just trained 1K to get the same results. Since the models were simple MNIST models, it was a fairly short training cycle per model, especially on large compute.

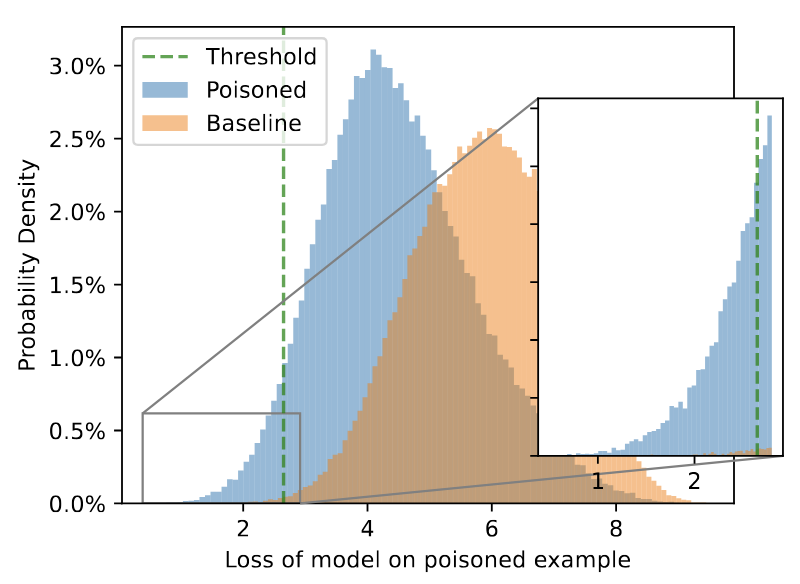

They trained those models so that they could use the loss information on the (outlier) canaries to successfully target them for MIAs. By gathering the loss for canary examples versus non-canary examples repeatedly, they slowly build two distributions.

Because these distributions have overlap (i.e. where the loss is similar or the same), they then optimize to find the exact threshold to separate these losses and identify the canaries versus the other examples. Below is a visual of their threshold findings.

Because finding this threshold shows significant privacy leakage for the canaries, this can be used to estimate epsilon bounds. Comparing this estimation with the paper, the authors concluded that the epsilon reported in the paper was not the true epsilon.

Like any good auditing team, this prompted them to investigate the code implementation, where they found a bug. The bug reduced the gradient sensitivity by batch size, which is incorrect. The batch size doesn't affect sensitivity of any of the gradients. The authors made the mistake because gradient clipping is calibrated by batch (adaptive clipping by gradient norm) but not the sensitivity.

Therefore the implementation was underestimating sensitivity and adding too little noise to counter the gradient information. This, in turn, left those canaries overexposed (along with any other points that needed more privacy). Getting sensitivity right in theory and in practice is a difficult job, which is why auditing is necessary. There's also continuing research on new attacks, meaning audits must be performed regularly4.

Let's say you are using an appropriately audited library. The next thing you might want to review is to make sure that you're using it correctly. To do so in a repeatable and adaptable way, you probably want to build testing into the usage.

Appropriate testing is hard

An obvious starting point is to actually test the produced models for the most common privacy attacks. Can you successfully run a MIA or a LiRA on the model?

Aerni et al (2024) reviewed recent papers on privacy-preserving machine learning and ran these tests against the implementations. To do so, they introduced canary inputs and then ran LiRA and MIA attacks on the resulting models. In their analysis of the results, they surmised that most of the papers were either cherry-picking results or taking the average attack on something like a mislabeled example versus a cleverly crafted canary.

As you have learned throughout this series, not all data has the same privacy risk. Some examples will be more prone to memorization because they are novel or represent complexity. It is useful to design privacy testing that takes this into account! One way to do this might be to evaluate sample complexity and example complexity as part of training and to select complex and interesting samples for future privacy evaluation.

As you also learned, mislabeled examples are easy for a model to unlearn/forget because they contradict information that the model will learn from the rest of their class/label/examples. Therefore, they are not a good use for testing real privacy concerns.

Outside of looking at risks for outlier and complex examples, it's also useful to think about what highly repeated examples are expected to be learned, and which aren't. If you get to know your task and data via unsupervised methods like clustering, this could show aspects of both of these types of examples.

Aerni et al make a few research recommendations which are also useful if you're a practitioner looking to appropriately evaluate differential privacy for your use case. They recommend to:

- Evaluate membership inference success (specifically true positive rate (TPR) at low false positive rate (FPR)) for the most vulnerable samples in a dataset, instead of an aggregate over all samples. To make this process computationally efficient, audit a set of canaries whose privacy leakage approximates that of the most vulnerable sample.

- Use a state-of-the-art membership inference attack that is properly adapted to privacy defense specifics you are using in your training (i.e. DP or otherwise).

- Compare your model to DP baselines (e.g., DP-SGD) that use state-of-the-art techniques and reach similar utility.

If you're a practitioner and you want to get inspired by their experiment's, take a look at the GitHub repository.

New approaches to testing have also helped move the field of privacy auditing forward. Nasr et al. developed an interesting approach that looks at auditing the training process as it is performed, meaning you don't have to wait until after you trained a model in order to get a good idea of what privacy guarantees you are offering.

In their work, they used a different type of attack to simulate the LiRA and state-of-the-art MIAs. They allow the attacker to observe the training process itself and to actively insert canary gradients5 into the process. Then, the attacker observes the loss created by these batches with and without canaries and trains a model to distinguish between them. They also present a weaker version where the process is only observed at certain intervals and there aren't canaries.

By evaluating the training process this way, they were able to determine better lower bounds for the privacy guarantees, meaning this research assists people choosing parameters that match the sensitivity they need. Not only that, you need to understand the upper bounds and the likelihood that you end up in the middle as Damien Desfontaines presented at PEPR.

Another interesting recent approach looks at the training process and tracks loss across epochs. Pollock et al. proved that looking at the distribution of losses across the training process can identify more than 90% of the memorized and at-risk examples. They also released their work on GitHub.

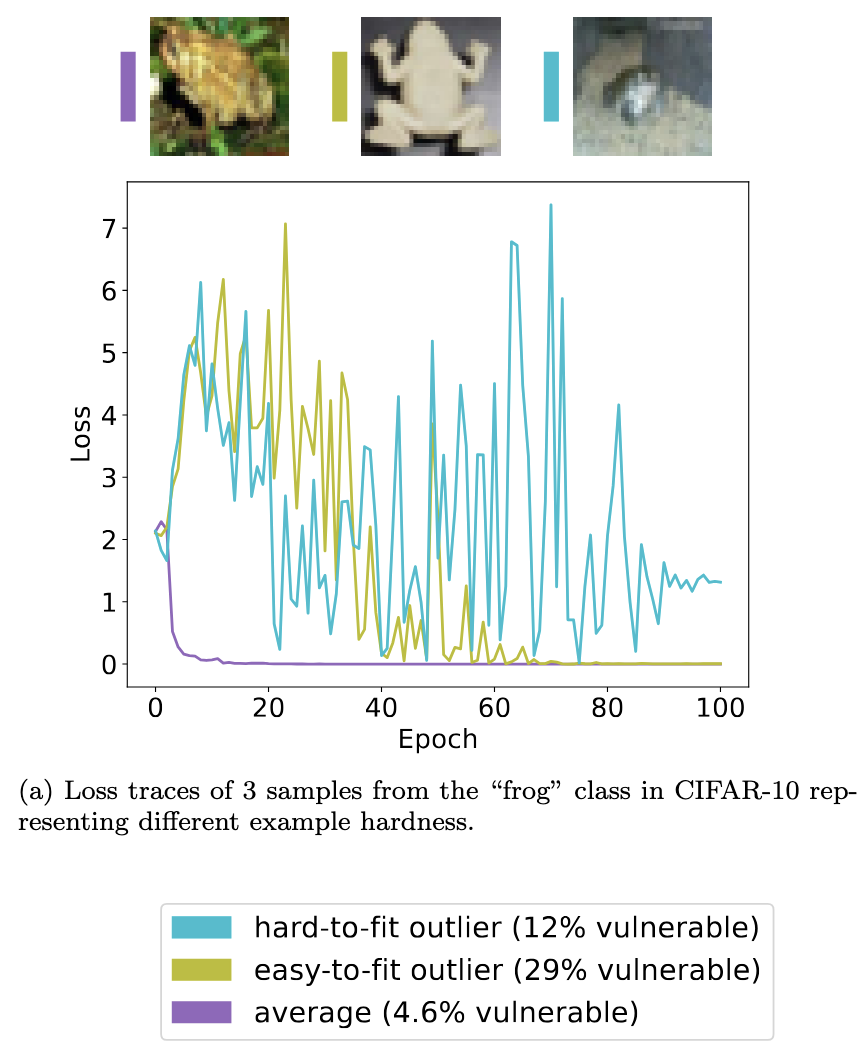

This is an example from their paper, showing three different types of frog images in CIFAR-10. One is average (lost in the crowd), one is an easy-to-learn outlier (not complex) and one is difficult to learn (complex). The authors also note the success rate of MIAs targeting these examples, showing that the outliers have a higher risk of being identified.

The loss traces are shown in the graph below, where the average example has a really stable and early decline in loss. The easy-to-learn outlier shows less stability in early and middle epochs, but eventually stabilizes. In comparison, the hard-to-learn outlier's loss almost never stabilizes. These are the indicators that the authors used (via sampling loss), to sort the outliers from the average and to understand the complex outliers versus the easier ones.

Ideally better testing like this example is easily accessible for practitioners. TensorFlow built some of these experiments and research work into Tensorflow code and infrastructure; however this repository might not be maintained in the future.

It would be useful to have these types of tests written into most of the major deep learning libraries, and into ML Ops and evaluation software. These tests should be easy to opt into and use, so privacy testing can become a normal part of ML/AI workflows.

Open research questions (aka kjam's wish list)

There are several unanswered questions when you take the theory of differential privacy and apply it in a real-world machine learning.

Research often uses toy datasets which sometimes have little to do with today's machine learning tasks. Proving that something works with CIFAR-10 doesn't necessarily tell me, as a practitioner, if this will help me fine-tune a LLM, or train a useful diffusion model with user-submitted art, etc.

Tramèr et al called for more realistic training examples that mimicked real-world use cases that require private training; such as learning with health data, or with the Netflix Prize dataset. Of course, it is difficult to create data that mimics real private data without actually releasing real private data.

Another open question I'd like to see in research is a better way to reason about the preprocessing steps and how to incorporate a holistic understanding of the privacy guarantees in an end-to-end ML system.

I'd also like to see better advice and research on parameter choice, differential private definition choices, noise choices and privacy unit choices. Although these significantly depend on the use case, there should be better research on pointing practitioners in the right direction for their use case. Papers comparing these choices using real-world tasks are rare.

Finally, as mentioned in the last section, there should be better ways to actually test privacy in deep learning systems as part of training and evaluation. And better ways to reason about what those test results mean for individuals.

In following articles, you'll dive deeper into other potential solutions, many of which are either new ways of framing the problem or research ideas. I'm curious... what do you think should be done about memorization and privacy risk in AI/ML systems? What potential mitigations do you find most appealing and why?

-

To dive deeper than this relatively high-level description, I recommend watching the paper presentation. ↩

-

There's strong critique of using Renyi differential privacy and DP-SGD in practice by Blanco-Justicia et al., 2022 where the authors experimented with several values of epsilon and delta, and also reasoned about what level of privacy this offered. ↩

-

There are also interesting applications for using canaries to audit other differential privacy tasks like synthetic data creation ↩

-

In research on auditing differentially private deep learning systems, Jagielski et al. uncovered how targeting private SGD with specific poisoning examples allowed them to more easily influence the model behavior even with the DP noise and clipping. ↩

-

The paper also tests different types of canaries and develops an algorithm for advanced canary generation. I think it's worth reviewing if you're thinking of building your own canaries and/or privacy testing. ↩